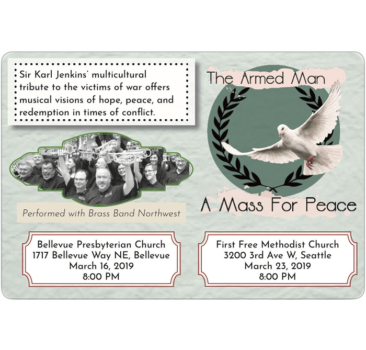

The Seattle Choral Company Proudly Presents The Armed Man: A Mass For Peace

Landing at No. 1 of a 2008 top-10 list of works by living composers in the United Kingdom was The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace by Sir Karl Jenkins. Commissioned for the new millennium and premiered in 2000, The Armed Man uses the medieval French song “L’Homme Armé” (The Armed Man) which was the basis of innumerable 15th- and 16th-century Mass settings.

It is an immediately accessible work full of memorable, neo-Romantic melodies, but there’s more to it than that.

The Welsh Jenkins sets texts from a variety of cultures and times to express the universality of the message that war is destructive and that peace is desirable. Psalms, the Revelation, the Muslim “Call to Prayers,” a poem by a Japanese witness to the Hiroshima bombing, the Indian epic “The Mahabharata,” and English poetry all play a part. The texts form a cohesive narrative—of prayer, preparation for war, battle, death, destruction, and mourning—that evolves into a declaration of peace and an affirmation that sorrow, pain, and death will be overcome. A few sections of the traditional Catholic Mass are skillfully interwoven into the sensitive musical setting.

The success of The Armed Man lies in Jenkins’s ability to underscore the vivid and often poignant texts through effective use of uncluttered vocal lines and clear harmony. Jenkins came of age in the 1970s progressive rock band Soft Machine, and he’s not shy to employ strong rhythms and soaring melodies.

Note: This article was written by an English chorister and reflects the point of view of someone who was involved in a community production of Karl Jenkins’ monumental choral work.

Karl Jenkins’ The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace is a powerful and poignant piece in the tradition of other British works such as Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem and Ralph Vaughn Williams’ Dona Nobis Pacem.

Rarely in my 20 years as a classical choral singer have I felt truly caught up emotionally in a piece. The first time I heard a recording of The Armed Man, I knew it would send shivers up and down my spine just to rehearse it.

This will be an emotionally exhausting piece to perform, as there are deep tonal contrasts between the harsh and disturbing war images and the hauntingly mournful and beautiful Mass elements. The piece has become all the more meaningful to me as I’ve researched its parts, and I hope what I’ve learned will encourage you to attend this concert and will help you better appreciate the work in its context.

Jenkins subtitled the work “A Mass for Peace,” but only four of its 13 movements are traditional Mass elements. This piece is not uniquely Catholic or even Christian. It recognizes what the preamble to the United Nations Charter calls “the scourge of war” as a universal human tragedy.

This work was commissioned for the millennium celebration by the Royal Amouries in Leeds, Britain’s oldest national museum. The museum’s master, Guy Wilson, selected the texts, which include Hebrew and Christian scriptures, an intoned Islamic call to prayer, observations of a Japanese eyewitness to Hiroshima and portions of an ancient Hindu/Indian epic. As Jenkins began composing, “ethnic cleansing” began in Kosovo, and Jenkins dedicated his completed work to its victims.

The title “The Armed Man” is the translation of a 15th century French song which found its way into many Masses of the Renaissance period. Its text translates as “The armed man should be distrusted; it has been decreed everywhere that each man shall arm himself with a coat of iron mail.”

The opening movement’s minor key is underlined by a military march percussion rhythm as bugles, fifes and drums build to the initial choral statement of the Armed Man theme, in French. The second movement is an Islamic call to prayer. Since in Islam there is no musical notation for this call, the interpretation is left to the cantor. A soprano solo opens a plaintive and penitent choral Kyrie. The men then intone Psalm 56:1-2 and 59:1 in a Gregorian style. The Sanctus is not the usual expansive praise of God but is mysterious and foreboding, sung to a march-step rhythm. Its glorias are like sun rays obscured by ominous gathering storm clouds; its hosanna with blaring trumpets reflecting the meaning of that Hebrew word is a plea meaning: “save us now.”

The next four movements describe war and its aftermath. In a Hollywood movie-style accompaniment, the chorus builds in heroic intensity through the first two stanzas of “Hymn Before Action” (1898) by Rudyard Kipling, the British poet of colonial empire. The text paints a picture of earth and sea poised to witness an epic battle, in expectation of glory and honor to be bestowed in life or death, and crescendos as troops invoke the aid of heaven: “Lord, grant us strength to die.” Another lengthy martial introduction, with faster tempo, precedes lyrics from John Dryden’s “A Song for St. Cecelia’s Day” (1687); distinctive are the trumpet call to arms and the “double double beat of the thundering drum.” Soon-to-be widowed women try to console themselves with “How blest is he who for his country dies,” words of the Roman poet Horace (23 BCE) translated by Irishman Jonathan Swift (Dryden’s second cousin) in a letter to the Earl of Oxford urging peaceable action in the face of hostilities.

Realizing too late that they are doomed, all the soldiers can do is desperately charge. The slaughter plays out in a glissando cacophony of random cries and moans by the chorus, instructed by the composer’s notation to “convey horror.” Following a long, eerie silence, a lone trumpet plays “Last Post,” the British equivalent of “Taps,” against the sound of rain. A bell tolls mournfully. The bleak text of the next movement is haunting enough by itself without knowing it is the memoir of Toge Sankichi, a 24-year old eyewitness to the Hiroshima atomic bombing who became a passionate peace activist before he died in 1953 of radiation-induced leukemia. Describing the mushroom cloud towering above and looking at the desolation and death all around, four solo voices over sinister, sustained strings finally observe, in macabre unison, “there smoulders a curse.”

The text that immediately follows would appear to be a seamless continuation of the last scene but actually comes from the Sixth Century BCE sacred Hindu/Indian epic “The Mahàbhàrata.” It describes an even older war of mythic proportions which, despite “civilized rules” attempting to limit the barbarity of war (much like the 1949 Geneva Conventions), ended in horrific atrocities and carnage. These two movements — “Angry Flames” and “Torches” — paint as ghoulish and ghastly a picture of torment and suffering as any flammis acribus of a Latin Mass’s Dies Irae Dies Illa — and without the images blunted by unfamiliarity with Latin. These are emotionally difficult passages to sing as well as to hear.

A lamentful Agnus Dei in larghetto tempo brings cathartic relief to singer and audience. The slow, reflective soprano solo that follows, its text by Guy Wilson, confesses grief and survivors’ guilt “now the guns have stopped.” A long, accompanied string solo introduces the molto largo theme of the lovely Benedictus, the last of the traditional Mass elements, its hosanna soaring fortissimo to high A in the soprano voice. This for me is the moment perhaps of greatest pathos in the entire piece.

The Armed Man melody is reprised in the last movement, but now in a major key, with a Renaissance dance rhythm, sung merrily, as words from 15th century Thomas Morley’s “La Mort d’Arthur” declare “better is peace than always war.” The chorus becomes human chimes as words from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s “In Memoriam A.H.H.” envision a more hopeful age ringing out “the thousand wars of old” and ringing in “the thousand years of peace.” Jenkins ends his work with a sumptuous largo, a cappella chorale based on the vision of Revelation 21:4 that, in the end, God will wipe away all tears, and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow nor crying nor pain.

“If I had to describe [my music], I would say that it sounds like nothing else, which is very satisfying. Much of classical music is still very isolated and narrow.” – Sir Karl Jenkins

Sir Karl Jenkins was born and grew up in the South Wales village Gower of Penclawdd, situated along an estuary where the villagers rake in phenomenal quantities of cockles for export to Europe. His great luck was in having a father who, as schoolteacher, organist, and choirmaster, gave his son music lessons. Jenkins received classical music training at Wales’ Cardiff University and at the London Royal Academy of Music. He went on to gain broad experience as composer, arranger, jazz performer, and band leader, acquiring knowledge of music spanning many centuries and traditions.

Jenkins first made his mark in jazz. On keyboard and oboe, he was a founding member of Nucleus, a pioneering prize-winning jazz-rock band. He later joined the psychedelic progressive rock and jazz fusion band Soft Machine, which was influential in the 1970s.

In the 1980s, Jenkins turned to a composing career in the field of advertising music, winning awards for music he created for many well-known companies, such as Levi’s, British Airways, Renault, De Beers, and Delta Airlines. In the mid-1990s, he entered mainstream music with the Adiemus project, which began as an experimentation with various vocal and instrumental sounds. The first three albums of the Adiemus series won phenomenal global recognition, topping both classical and popular music charts and winning 15 gold and platinum awards. World-class singers, such as Kiri Te Kanawa and Bryn Terfel, have recorded some of his vocal music. Jenkins has received many commissions from such prestigious sources as the Royal Ballet, the London Symphony, and HRH the Prince of Wales. His scoring of the documentaries “The Celts” and “Testament” has won him British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) gongs, the British equivalent of Academy Awards statuettes.

Classic FM, the U.K.’s foremost classical radio station with six million listeners, conducts annual listener surveys to determine the most popular classical composers. Shortly after the 2000 premiere of The Armed Man – A Mass for Peace, the work claimed the eighth slot in the top-10 list, placing Jenkins as the only living composer among such greats as Mozart and Rachmaninov. “I don’t think of myself as within a million miles of the composers I’m surrounded by. It’s just that people have responded to the “Benedictus” from The Armed Man, and it has proved quite popular.” The Armed Man CD was released on September 10, 2001, the day before world-changing events that led to another war.

Jenkins continues to explore fresh sounds, blending genres, cultures, and historical periods, creating music that draws an ever-broader audience. Soon after its 2005 release, his Requiem topped the classical charts. That same year, The Armed Man CD went gold, selling more than 100,000 copies, and has had hundreds of performances in the U.K. and Europe. Jenkins would like this work to receive more U.S. exposure as well. His many awards – from a room named in his honor at the Royal Academy of Music to Officer in the Order of the British Empire (OBE) by Her Majesty the Queen – do not distract Jenkins from focused productivity. His Stabat Mater premiered in 2008 in Liverpool.

Late in 2004, a pair of British musicians, Andrew Wainwright and Duncan Gibbs, had a flash of inspiration. As part of the final year of their music degree at Middlesex University, they would transcribe Karl Jenkins’ immensely popular The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace for brass band, choir, and organ, and present a concert of it. Wainwright set about arranging the brass parts, while Gibbs augmented the score with the addition of an organ part. It was not long before the arrangement was approved by both Karl Jenkins and Boosey & Hawkes, the publisher. This version had its premiere performance in April 2005 in the presence of Karl Jenkins and becomes the basis for the Seattle Choral Company’s collaborative performance with Brass Band Northwest, here in Seattle.

Comparing the two versions reveals what an excellent job Wainwright and Gibbs have done, and there are very few instances where the new version is in any way inferior. One is aware of certain differences, such as the lighter tubular bells at the start of “Angry Flames” replacing the deeper tolling bells of the original. There are remarkable similarities in instrumental tone, with judicious selection of brass or organ accordingly. Perhaps most importantly, the accompaniment never overshadows the singing, whether solo or chorus.

Wainwright and Gibbs are to be commended for their work, which could be the answer for other bands wanting to arrange joint concerts with a choir, and looking for something more substantial than the “March of the Peers” or “The Lost Chord”. According to SCC director, Freddie Coleman, “The whole idea of presenting Jenkins’ work here in Seattle in this arrangement is owed to Judson Scott, the current director of Brass Band Northwest. Judson and I met quite frequently beginning in the summer of 2017 to iron out all details and forge a unique relationship between our two organizations.”

Brass Band Northwest (BBNW) is composed of professional, semi-professional, and amateur musicians who rehearse weekly and perform five major concerts a year. In addition, Brass Band Northwest has performed for a variety of events including the Leavenworth Christmas Lighting Festival, Yarrow Point’s Independence Day Celebration, Pioneer Days in Tacoma, Bellevue Botanical Garden’s “Music in the Garden,” and Seattle Mariners games. Brass Band Northwest has also appeared on 98.1 KING-FM for Northwest Focus Live and performs for Bellevue Presbyterian Church services four times per year.

Brass Band Northwest was founded in 2002 by Steve Keene and Dennis Schreffler, with the goal of sharing the vibrant and exciting sound of all-brass music with audiences of all ages in the Pacific Northwest. Brass Band Northwest is grounded in the tradition of the British brass band, but explores a wide range of musical genres.

Brass Band Northwest hosts the Northwest Brass Festival each year, presenting brass bands from California to British Columbia. The day is full clinics and performances with internationally recognized band clinicians and guest soloists.

Go to the Brass Band Northwest web page for more information.

The British brass band dates back to the early nineteenth century and England’s Industrial Revolution as an outgrowth of the medieval waits. With increasing urbanization, employers began to finance work bands to decrease the political activity with which the working classes seemed preoccupied during their leisure time. Brass bands in Great Britain presently number in the thousands with many of the bands having origins prior to 1900. Originally the bands were funded by coal mines, mills, and many today retain corporate sponsorship.

What makes the British brass band unique? All the brass music (with the exception of the bass trombone) is scored in treble clef, a characteristic that over the years has allowed for remarkable freedom among certain bands, making the transition from one instrument to another somewhat easier. The number of members (instrumentation) is rigid, usually limited to between twenty-eight and thirty players, but the repertoire is unusually flexible, with concert programs consisting of anything from original works, orchestral transcriptions and featured soloists to novelty items, marches, medleys, and hymn tune arrangements. With the exception of the trombones, all instruments are conical in design, producing a more mellow, richer sound, yet one that has wide dynamic and coloristic variety. The term “brass band” is not entirely accurate, since brass bands also normally include up to three percussion players who are called upon to play as many as twenty different instruments depending on the demands of the music. Standard acceptance of more than one percussionist in the brass band is really a phenomenon of the last forty years, but one that has added immense challenge, interest and variety to the sound.

Although brass bands were also an important part of life in nineteenth-century America, they were superseded by larger concert and marching bands. However, many fine historic brass bands are still actively performing today. During the course of this century the Salvation Army were predominantly responsible for maintaining the brass band tradition in America through their music ministry. Only in the last fifteen years has a brass band resurgence begun in North America. The formation of the North American Brass Band Association (NABBA) has been crucial and influential in the renaissance.

Original works from Holst and Elgar to modern-day composers such as Philip Sparke, Edward Gregson and Joseph Horovitz have resulted in a growing and dynamic repertoire. American composers such as James Curnow, Williams Himes, Stephen Bulla and Bruce Broughton all got their start writing for brass bands of the Salvation Army and are currently writing brass band music in addition to their other compositions for band, orchestra and film scores.

There are presently several hundred brass bands in North America, many affiliated with NABBA, and it is not only exciting to see the tradition making a return, but also such a valuable and unique contribution to the rich musical heritage of this country.